You might be surprised (it surprised me when I began helping other teams as a coach), but most developers commit code to version control only about 2 or 3 times a week.

This limits the frequency with which they can deliver working code to production.

When our goal is to increase the frequency of delivering value and, therefore, practice trunk-based development, continuous integration, and continuous delivery, we seek the opposite: to accelerate the frequency of our commits, as much as possible.

This practice, known as micro-commits, is, along with automated testing and build automation, one of the fundamental engineering practices if we want to achieve continuous delivery.

Save the Game

We need to view commits as if we were saving the game in a video game.

We aim to avoid losing progress as much as possible. We don’t want to respawn seven screens back and have to go through all those screens again. In other words, if we die, we want to respawn as close as possible to where we died. With commits, the concept is the same.

We can commit for things as small as:

- Formatting a file

- Renaming a variable

- Extracting a method

- A small functional increment

- Adding a new test case

- Adding a dependency

- A configuration change

- etc., etc.

A good rule of thumb is to commit between 5-20 commits per hour. In general, the more, the better.

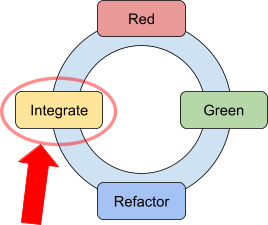

Micro-Commits and TDD: The Extended RGR Loop

When doing TDD, there is a perfect time to make a commit: when we finish an iteration of the red-green-refactor loop.

Each iteration of the TDD loop adds a small functional increment, leaving us with passing tests: it’s the perfect time to save the game.

This technique is known as the Extended Red-Green-Refactor Loop or red-green-refactor-integrate loop.

We can even commit immediately after reaching green, and then integrate as many times as refactoring steps we take (remember that refactoring is performing a series of small transformations that preserve the behavior of the code, meaning we never let tests break, i.e., go back to red).

It is not good practice to integrate immediately after writing a test before it passes, as if we commit in red, we’ll be breaking continuous integration.

What if the build takes too long?

A scenario that may hinder us from integrating more frequently is if tests take too long to run.

In this case, we will prioritize addressing the root cause, trying to reduce the duration of the tests, rather than integrating less frequently.

Graceful Retreat

If integrating more frequently wasn’t reason enough to use micro-commits, there is another very interesting benefit: the ability to make a graceful retreat.

When we break the code when adding a feature or refactoring (we reach red), we have found that it is easier to roll back to a known state (go back to green) and, from there, move forward again, taking a different path, than trying to go back to green directly by fixing the errors.

It is a more consistent and predictable strategy, and also more rewarding in terms of mental health. Therefore, we want the point where we revert to be as close as possible to the moment we broke the code, to lose as little work as possible.

This way, after reverting the changes, we take the opportunity to analyze what went wrong and develop a more suitable refactoring strategy that does lead us down the path we are looking for.

Conventional Commits

A technique not directly related to micro-commits but that works well when used together is the conventional commits standard.

It is a convention for writing commit messages that poses a feature that synergizes with micro-commits, and that is that it obliges us to define the commit type.

That is, in the commit message, in addition to adding a description of the change, we force ourselves to accompany it with an additional field: the commit type.

This type can be a series of known values, among others:

- feat: for new features,

- fix: for bug fixes,

- test: for new tests (whenever it’s green, let’s avoid committing in red),

- refactor: for changes that do not alter the code’s behavior,

- chore: for other changes that do not alter the source code,

- style: for style or formatting changes,

Adding the type to each commit invites us to ensure that each commit has a single responsibility, that it does only one thing. For example, if in the same commit we add a new feature and fix a bug, what type would we give it?

Asking ourselves this question leads us to another: how could we have made this change in two separate commits, each of a different type? This would lead us to make two smaller commits, and therefore to more continuous integration.

In Summary

Micro-commits are a prerequisite for truly practicing continuous integration, a practice that is often overlooked by many teams but is very easy to learn and apply. If we are doing TDD, practicing micro-commits feels much more natural, as we have well-identified moments to integrate the code. When we are refactoring, it helps us keep the code always green and be more productive. A very good way to start applying micro-commits is to use the conventional commits standard to force ourselves to make smaller changes.